//CN: This isn’t a design blog where I go through the in-depth design decisions that made Earth Rising the game it is today. This is the personal and emotional story of how I created the game. It delves into the depressive state and hopelessness that lead up to its creation, how a small spark created a huge change in my life, and how we hope the game will inspire changes in the lives of others.//

Sometimes, to make change, all you need is the right spark.

November 2019 was what I would call the birth date of Earth Rising, (although it wasn’t called that at the time, and it didn’t develop from more than a sketch for months afterwards). For a game concept about hope and transformation, it’s interesting that it came out of what was, for me, a very dark time.

It began with the collapse of Stop, Drop & Roll.

“Wait,” you might think, “Isn’t that your company? Seems pretty alive and well to me!” and sure, it is now, but at the time the partnership it was built upon had dissolved, the plan we had made to publish Pugs in Mugs had halted, and the vision I’d had of becoming a board game designer and publisher seemed to be in tatters. Hindsight is 20/20, but at the time I was feeling pretty depressed. The future I’d so eagerly anticipated, and been willing to put my all into in order to make real, was to be replaced by the job-hunt grind I’d already spent three years trying to make anything of. I’d recently been diagnosed with autism, and had been found as a kid to have dyslexia, dyscalculia, dyspraxia, and ADHD. In plain speak, my brain didn’t do the writing, reading, numbers, or movement like a regular human. I was not what anyone would consider a good hire.

My partner Rhi, who at the time had just begun her masters degree, invited me to go out with some friends and see an indie documentary about the climate crisis, and I couldn’t have been more reluctant if I tried. What was the point in learning more about another hopeless future? The true nature, and urgency, of the climate crisis had become publicly clear at that point, mainly thanks to ‘Extinction Rebellion’s’ movements in London and Brighton, where I live. Brighton is run by the Green party, and information and activism on the climate crisis was rife throughout. It was inescapable. And the overwhelming message was clear - we must act, otherwise it’ll be too late and we will all die.

Not exactly the message you want to hear when you’re already low on hope, you can imagine, no matter how important it was to say it. Worse still, our national election was coming up fast, brought about early after the second promise in a row to not rerun the election was broken, and despite the intense need to change our country to fight the climate, the desperate cries of the working class to raise the minimum wage, and the rampant homelessness, with even our middle class reportedly relying on foodbanks, the polls were insistent that the one party that had no interest in such things would win. Again. After over ten years of causing these problems in the first place. It seemed to me that whether it was in a personal context, a national context, or even a worldwide context, the message was clear: Everything was only going to get worse, and there’s nothing we can do about it.

Yet, what else was I going to do? Submit my CV to another ten jobs I might not hate, wallow in self pity and wish I could afford to drown my sorrows? At least this documentary was about something I cared about, and I might get along with the people we were meeting. So, sure, I said. I’ll go.

2040 is a documentary by Damon Gameau, Australian actor and activist, and his message was a simple one: I have a child, and the outlook is bleak, and I worry first and foremost for her future. Is there anything we can do to change her future?

Spoiler alert: The answer is yes.

The film explained the situation first, but quickly moved on to the things we could do - in real life, no science fiction or untested concepts allowed - to reverse the damage and make life better for everyone. It talked about concepts like Doughnut Economics, sustainable and distributed energy, regenerative agriculture, marine permaculture and electric vehicles, and how their adoption would drastically cut down how much CO2 and methane we were putting into our atmosphere. Even more, it showed how our ecosystems were closely connected, and how the revitalisation of one fed into the others, bringing everything back, making both our planet safer and our lives genuinely better.

I was in tears when the film ended.

It had given me a feeling I hadn’t really felt in years; hope.

I not only had a clear understanding that the problem was fixable, that we could reverse our own shortsighted nature of consumption and destruction and it wouldn’t be too late, but it also gave me the understanding of “How”.

It was the combination of these understandings that made me see, clearly, like a mirage of interconnected cogs and wheels, how to transform this knowledge into a functioning, interactive, co-operative game. Sure, my company was up in flames, and sure, I had no idea if I’d be able to do anything with it, or if there was any interest in such a game, but I couldn’t shake the idea. Later that night Rhi asked me, “Are you okay? You’ve been very quiet since the film.”

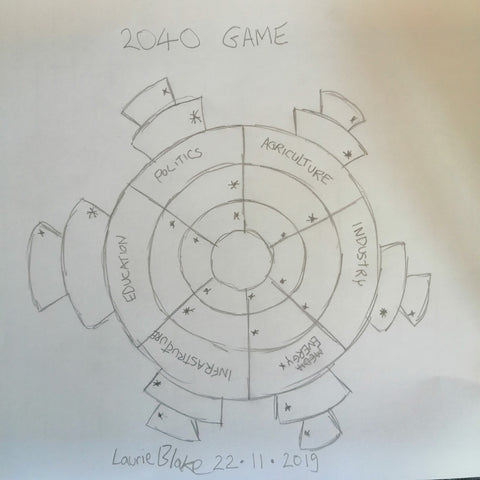

I tried to explain, in my haphazard way, of intersecting ideas of the burdens on our world laying around a board that fills in as you succeed. Of CO2 and methane and other problems being taken off and people being helped and how it all works together. Of different sectors that all overlap, all depending on each other, giving different powers, how each one had practices with two sides, one sustainable that made things better and the other unsustainable, making things worse.

She didn’t get it. So I drew it. And then it made sense.

And that, I felt, was what made the difference. Nobody wants the world to end, right? Everybody wants things to get better, even if only for themselves, they want improvement. There’s just so much information out there, all conflicting, all claiming credentials, and yet ultimately it’s overwhelming. How can you get a sense of the bigger picture when there’s so much to see?

You need an overview. A picture of how the engine works, and how we affect it. Because if we’ve affected it like this before, we can do it again. If we, as a species, have the power to change the atmosphere of an entire planet, then is there anything we can’t do?

I spent my evening that night putting together a document outline how it would work, the basic turn structure, the way “carbon” as it was then referred to, was generated and removed, and how people went in and out of poverty. To this day, most of it matches that document.

Rob Ingle, my fellow company director and aggressively enthusiastic co-conspirator, approached me a month later and said, “Let’s do it. Let’s make Pugs in Mugs happen.” and my father, Jasper, offered to join and help me with the business side. As the origin of my love of board games, he certainly had the enthusiasm, and together with Rhi we embarked on a quest to make board games.

And then Coronavirus shut down the world.

Waap-waaah. Sad trombone, right? Well, screw it, we thought, it’s not “harder” if you haven’t done it before yet, so let’s do it anyway. And we did. And we succeeded. It was terrifying and amazing and we learnt more together than I think we could have imagined but we did it, and now Pugs in Mugs is being shipped to everyone who believed in us!

After our campaign succeeded, I didn’t really stop for breath. During the Kickstarter campaign, I’d used my free time to create a prototype of what was then called “2040 the board game”. We put it together in Tabletop Simulator with ugly, block colour prototype art and we tested the heck out of it. It worked, and it was even fun! Players worked closely together, planning and discussing their turns and crying out in horror when a Status Quo was drawn. The asymmetrical character abilities weren’t easy to refine, but we got there. Back then it was just sectors and numbered tokens, Agriculture 1 to 7, Industry 1 to 7 etc, but it still worked well as a game.

In between getting Pugs in Mugs ready for manufacturing, I began to dive into my research about what exactly those seven practices would be, both sustainable and unsustainable. The work was gruelling, and at first it was often depressing. I was learning more and more about the ways we were abusing our world, and each other. And it’s hard, when you only look at all of that, to stay hopeful. It’s exhausting to take it in. That’s just a snapshot of the problems we face, yet even that’s a lot. Which is why, I had to keep reminding myself, over and over like a mantra… focus on the solutions.

Yes, these are problems, but it’s not enough to highlight them. We need to focus on what we can do about it. The idea that we can change it, and with enough of us calling for those changes, we can make them happen.

I put it all together into Earth Rising and made it as close to reality as I could. Then I started reaching out. I didn’t know how to contact 2040, who were over the other side of the world in Australia, but I did know that Kate Raworth was in the UK. So I tweeted her. It was terrifying! I was just a fledgling board game designer with a passion, she was the real deal. Yet she said yes, she’d love to take a look, and a month later I played the game on Tabletop Simulator with Kate Raworth, her daughter, and her team. And they loved it!

They advised me on how to make it better - how the ecological burdens were too singularly the responsibility of the sector they were over, and how people being supported in their lives, in a sustainable world, shouldn’t just be dependent on jobs. Practices support people, they said, but green electricity doesn’t just provide for the people working those jobs. These and their other insights, the knowledge that comes from understanding and working with these processes in the real world, were invaluable. We still had to balance it out, keeping the game a joy to play first and foremost, not letting it get overcomplicated, but such are the challenges of any design!

After we made the changes, Kate put us in touch with the 2040 team. This of course led to a playtest together, arranged across an almost 24 hour timezone difference. They were blown away by the game we’d made. Between the ease of play to the depth of strategy, they loved how comprehensively the game allowed an overview of the situation without overly simplifying it.

It was around this time that we settled on the name ‘Earth Rising’ and the tagline “20 Years to Transform Our World”.

I decided that it wasn’t enough that Earth Rising be a game that had all this information nestled in amongst a great game. I wanted it to be more, and to be a part of making that transformation happen for real. I discussed with my team about how, by donating a significant portion of our profits to charities, we could make our game not only show people how to reach a sustainable future, but to be, through us, their first step towards making it happen.

I began approaching charities about enlisting their help to make Earth Rising as incredible as it could be. It didn’t prove as easy as expected, with many industry and infrastructure charities in particular being too busy to spend time helping out a board game. But we persisted, and found a group of interested charities and not-for-profits willing to put the time in to help us collate accurate and engaging source material. Everything was coming together, and with the illustrations transforming the game into its final edition, we set about making certain that each sector’s practices were problems and solutions our planet faced in the real world, and upon changing would make a major difference - both in and out of game.

Now here we are, putting our production and learning out into the world! So many exciting and passionate people have joined us on this journey, and it fills my heart to see how far we’ve come. My favourite thing about designing a co-operative game was how it brought players together, but as we’ve engaged people with our game and it’s theme, it strikes me that Earth Rising bridges the gap between two worlds - the environmental; filled with compassion, empathy and fury, and the gamer drive to win; filled with determination, creative thinking and focus - and if there’s one thing I hope is the result of this, it’s that they both learn from each other. Perhaps they’ll combine forces and create the community driven change our world is crying out for!

(This blog post was originally posted on May 24th 2021)